Sunday, November 04, 2007

Tina Rosenberg goes to school on Venezuela's oil, and flunks

An interesting dichotomy has developed with respect to Venezuela. With a highly popular president and a booming economy the place has become, at least for the moment, downright boring. On the other hand, some in the international media seem to think that Venezuela’s economy is near collapse, its president virtually a dictator, its society is facing social convulsion, and its people can’t find enough food to eat.

Fortunately for Venezuela there really isn’t much more to this dichotomy than some pretty poor reporting. Case in point is “The perils of Petrocracy” in today’s New Times.

The first problem with the article is it is a fairly large bait and switch. It starts off as if it is going to be about the economic problems that countries with lots of oil run into and whether or not oil is a help or hindrance for their economic development. That is certainly an important topic. Yet the article gets side tracked into a discussion of the current state of the Venezuelan oil industry and never gets back to the subject of oil and development. But more on that later.

Unfortunately even though the article is mainly about the Venezuelan oil industry it doesn’t even prove very informative about that as the author, Tina Rosenberg, clearly failed to do her homework. She doesn’t bother to familiarize herself with all the readily available information on the subject and when she talks to the former overlords of the Venezuelan oil industry – who just maybe have an axe to grind – she doesn’t even know enough to ask the right questions or bring up key facts which might cast doubt on their assertions.

For starters there is this complete misunderstanding of what the dispute over the oil industry is really all about:

Here Ms. Rosenberg has completely confused the issues of what Venezuela should do to develop economically – i.e., how should it use the oil revenues that it gets – with the other very hotly debated topic of how Venezuela should maximize it oil income – i.e. how should Venezuela use the abundant oil it has in the ground to generate the greatest amount of income. The dispute over how the state owned oil company, PDVSA, should be used is NOT between pumping more oil or “producing Bolivarian socialism” but between pumping more oil just to have a bigger oil company or pumping less oil to have higher oil prices and hopefully more revenue for Venezuela.

In other words should PDVSA try to become as big as Exxon-Mobil, even if it generates less revenue for the country in the process, or should Venezuela be a good member of the OPEC cartel and restrict oil output to increase the amount of money they get for their oil?

That debate, the REAL debate regarding oil policy, has been going on in Venezuela for 40 years now. Before Chavez came to office those who just wanted to grow PDVSA had power. They were notorious OPEC quota busters (Venezuela was producing 700,000 barrels per day over its quota when Chavez came to office). Their quota busting policies helped push oil prices steadily lower in the 1990s and in turn sent Venezuela’s economy into a tailspin.

So unaware of this is Ms. Rosenberg is she never once mentions either OPEC quotas or the effect that the level of Venezuelan oil production might have on prices. Prices are presumably set only by outside forces that Venezuela has no control over at all and so it doesn’t even merit thinking about or discussing. In this, she accepts, either consciously or unconsciously, the most fundamental tenet of the anti-Chavez former managers of Venezuela’ oil – that as Venezuelan production levels have no impact on prices and prices should therefore be taken as a given, the only logical policy is to maximize the amount of oil produced. That many other Venezuelans thought differently, including the ones who made Venezuela a founding member of OPEC, completely escaped Ms. Rosenberg’s notice.

Chavez himself of course knew all about those debates and was a firm believer in working with OPEC to restrict production, boost prices, and maximize oil revenues, NOT production. Upon coming to office in 1999 he immediately cut Venezuelan output sharply to conform with OPEC quotas and in the process almost tripled oil prices and greatly increased Venezuela’s oil revenues. The old guard PDVSA management never accepted this and almost immediately set about trying to overthrow his government.

That Ms. Rosenberg doesn’t even understand what the heart of the dispute is – should the country maximize oil production or should it maximize oil revenues and its corralarly of should it ignore OPEC quotas or follow them religiously – leads the entire article astray. Moreover, by not appreciating how contentious this debate has been she doesn’t take sufficient care to verify peoples assertions on the what Venezuela’s industry is like.

For example, she clearly swallows the erroneous assertion that Venezuela was a well run oil producing machine before Chavez and is now much less efficient hook, line and sinker. She bases this belief not on any actual analysis but probably on getting most of her information from the PDVSA management that was fired by Chavez.

In reality, before Chavez PDVSA was highly corrupt and it was that corruption which led them to want to maximize production.

In the early 1990s when PDVSA embarked on a course of ignoring OPEC increasing production, profits be damned, it was led by Andres Sosa Pietri. In his book “Petroleo y Poder” (a book that should be read by anyone with even a passing interest in the Venezuelan oil industry but was obviously not read by Ms. Rosenberg) he lays out his beliefs that PDVSA should be run free of any control by the state, that production should be maximized, and that Venezuela should leave OPEC.

He also, in a bout of honesty, notes that his family owned the Constructora Nacional de Valvulas (the National Valve Fabricator) which made all the pumps and valves used by PDVSA as it expanded production. This is a stunning conflict of interest (and it should be noted that the shareholders of a private corporation would never tolerate such a clear conflict of interests) and makes it more than obvious why he would want to maximize production – the country might make less money but all the new PDVSA investment would, and did, make his family wealthy.

Later the company was run by Luis Giusti. He believed in ignoring OPEC and maximizing production just as much as Sosa Pietri did. He also believed in opening up Venezuelan oil exploitation to private firms whose long term, favorable contracts would, as Bernard Mommer (another key observer of the Venezuelan oil industry who Ms. Rosenberg has apparently never hear of and never read) noted, help force Venezuela to leave OPEC.

Mr. Giusti was no less self-serving in his policies than was Sosa Pietri. During his tenure most of PDVSA’s finance and administrative functions were spun off into a private for profit company called Intesa which Mr. Giusti had direct financial interests. Of course, the bigger PDVSA became the more profits there would be for Intesa and for Mr. Giusti himself. So once again we see that PDVSA’s policy of hyper growth most likely grew out of a desire not to help Venezuela but rather to help the top management of the company enrich itself.

So this morass of insider dealing and corruption is what we are supposed to believe was a “sleek machine” and an “excellent exploiter of oil”? The reality is this quota busting, production maximizing company only made its management wealthy while the revenues for the country continually shrank.

Ms. Rosenberg accepts much of the rest of the old PDVSA management’s propoganda. For example, while noting that Citgo may have been used to move oil profits out of Venezuela through transfer pricing (for a discussion of how that worked see Mommer’s article Subervise Oil) she then gushes that both the Citgo purchase and the opening up of production of the heavy oils in the Orinoco Belt were “brilliant business decisions”!

Let’s see how “brilliant” these business decisions were. First, Citgo was purchased without bothering to negotiate a double taxation treaty with the U.S.. This was then used as an excuse for Citgo never to pay any dividends to Venezuela and in fact prior to Chavez coming to office Citgo never paid any. So Venezuela had a multi-billion dollar investment which was not giving it any profits. It is hard for me to see the “brilliance” of that.

Rosenberg then buys into the spurious argument that Citgo refineries would help assure a market for Venezuelan oil. She is apparently unaware that many of the Citgo refineries, and other refineries that Venezuela bought in places like Germany, have never actually refined any Venezuelan oil.

Worse still, this betrays a lack of understanding of basic economics. If Citgo refineries were somehow specially suited to refine Venezuelan oil, which some of them are, they would be buying Venezuelan oil no matter who owned them. In fact, Venezuela recently sold off one of its Citgo refineries in the U.S (one that cost Venezuela $750 million in losses by being forced to sell it under priced oil) and guess what? - it still buys its oil from Venezuela. Venezuela no more needs to own Citgo to sell its oil in the United States than Sony needs to own Best Buy or Circuit City in order to sell its televisions in the U.S.

The Orinoco Belt oil production, which was ramped up to 600,000 barrels of oil per day was the other half of this “brilliant” decision. Yet it only appears brilliant to Rosenberg because she completely ignores the issue of OPEC quotas. If there were no quotas and if Venezuelan output had no effect on prices then maybe having this additional oil revenue would make sense.

However, Venezuela does have an OPEC quota which limits what it can produce. For that reason this Orinoco oil, which is expensive to produce and fetches a lower price on world markets making its profit margin much lower then other Venezuelan oils, displaces other oil. That is, if Venezuela’s quota is 3 million barrels and the Orinoco oil is 600,000 then they have to cut back their other, more profitable production, back to 2.4 million barrels. No normal person would view cutting back on the production of more profitable oil to make way for LESS profitable oil a “brilliant business decision”.

Of course, the real brilliance of the decision from the perspective of people like Sosa Pietri and Giusti was that turning over oil production to private companies would force Venezuela out of OPEC as private companies would never agree to cut their output to stay within quotas. In fact, the co-owner of the Citgo refinery that Venezuela just sold, Lyondell, sued Venezuela in 2002 for cutting back its oil allotment due to OPEC quotas!! If Ms. Rosenberg had bothered to read Sosa-Pietri’s and Giusti’s writings on these subjects she would have known this. But once again she is so unaware of what the issues are she is incapable of even asking the right questions and categorizes as “brilliant” decisions which in fact were disastrous for Venezuelan.

Rosenberg then veers into talking about how “PDVSA” is in trouble”. According to Rosenberg one prime example of “trouble” is “the mystery of the missing drilling rigs”. Venezuelan oil production is falling, she claims, because Venezuela supposedly does not have enough drilling rigs to drill for oil and maintain production which naturally declines as old wells run dry.

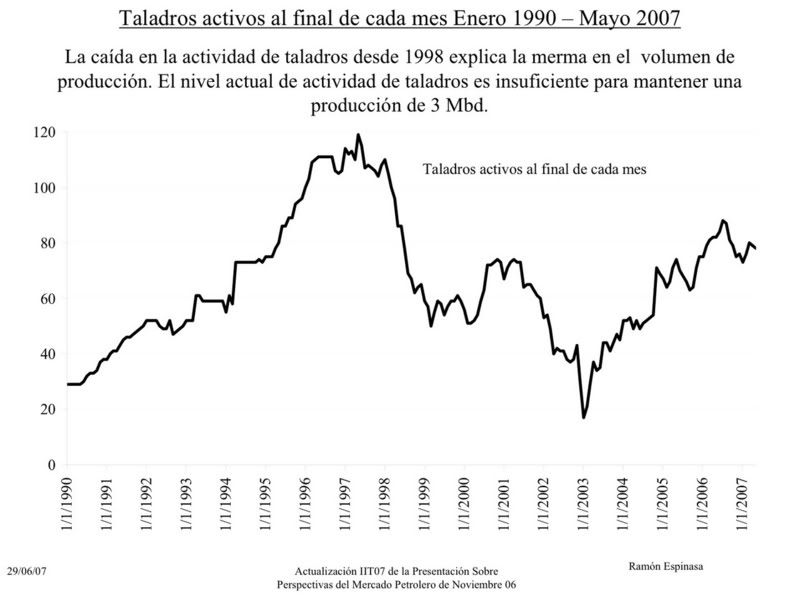

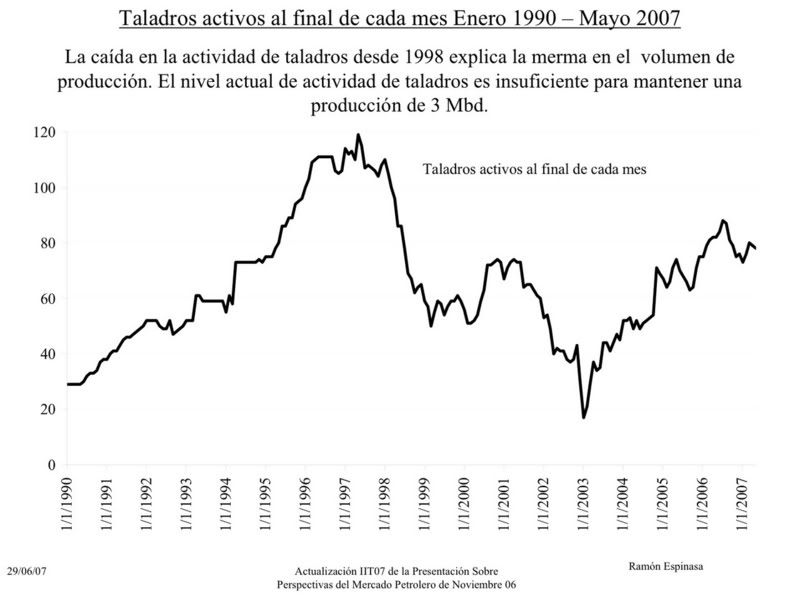

To analyze this mystery we fortunately have at our disposal a chart of oil rig numbers in Venezuela prepared by one of Rosenberg’s main sources, the anti-Chavez former PDVSA economist Ramon Espinasa:

The text on this chart says that the current number of rigs is insufficient to maintain a production level of 3 million barrels of oil per day. Yet the numbers in the graph itself show that claim to be false. Looking at it we see that the current number of drilling rigs is equal to or greater than any time except the period between 1995 and 1998. From 1995 to 1998 Venezuela was very rapidly expanding oil production (ie not just maintaining production but increasing it by about 200,000 barrels of daily production every year) to well over three million barrels per day. Given that Venezuela is not currently expanding production (because it has to stay within its OPEC quota) it does not need that number of rigs.

However note that from 1999 to 2002, when the country was simply maintaining production and not expanding it, the number of rigs was actually somewhat LESS than it is today. With around 80 rigs Venezuela managed to keep production levels of around 3 MBPD from 1999 to 2002 so why should that number of rigs all of the sudden be inadequate? The fact is, comparing the number of rigs to what Venezuela’s needs are we see that today’s number of rigs is perfectly adequate to maintain production levels.

Should Venezuela want to significantly expand production, as its long term business plan calls for, it would need more rigs, but given OPEC quotas that is not likely to happen any time soon.

So what we see is the only thing mysterious here is why Ms. Ronsenberg hasn’t better informed herself on these issues and even looked closely at the number presented by her favored sources before giving what is clearly an erroneous analysis.

Continuing on with her “PDVSA is in trouble” theme she then quotes one analyst as saying PDVSA production has been going down for the past couple of years – presumably because of mismanagement and missing oil rigs! Of course, that Venezuela might have intentionally reduced its production to meet cuts in its OPEC quotas over the past two years completely is completely beyond her. Yet that is precisely what happened. Once again, the fact that she barely seems to realize that OPEC exists and what Venezuela’s relationship with it is makes it almost impossible for her to get much of anything right in this article.

As Ms. Rosenberg clearly wasn’t doing any independent verification of facts and was relying on the fired PDVSA managers for most of her information I had to wonder when she was going to get to the biggest two canards surrounding the Venezuelan oil industry – that PDVSA is no longer transparent and that its oil production is much less than what it says it is. I didn’t have to wait long.

First she starts with “[PDVSA] has become less and less transparent”. She goes on to say:

One thing I’ve always wondered about this whole transparency discussion is if a company publishes financial statements and no one bothers to read them does it really do much for transparency? The reason I pose that question is because, as will become clear shortly, Ms. Rosenberg obviously did not read any of PDVSA’s financial statements.

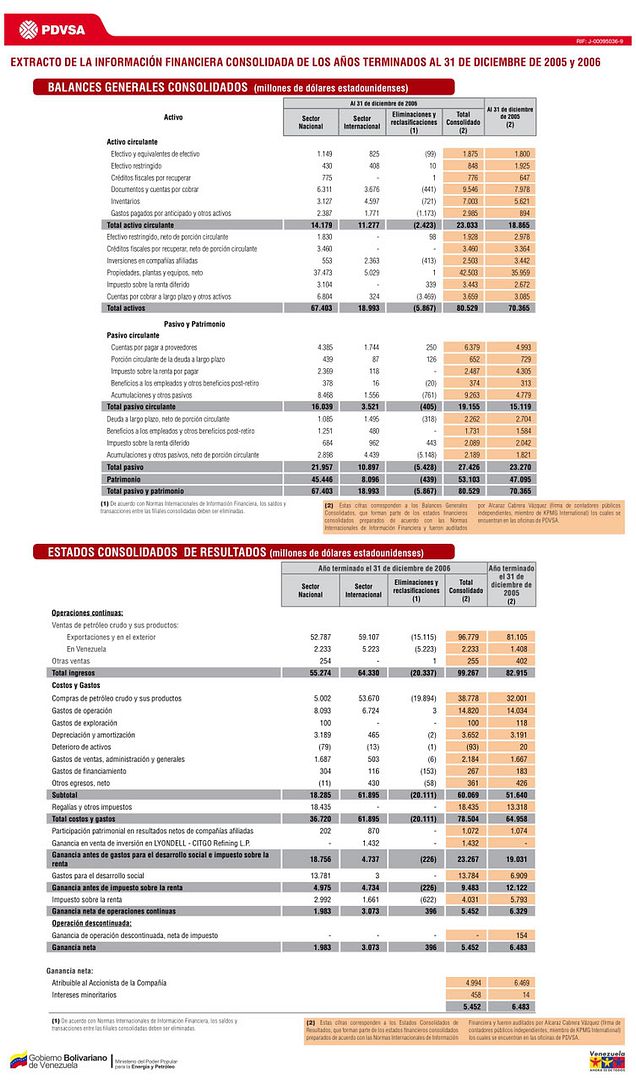

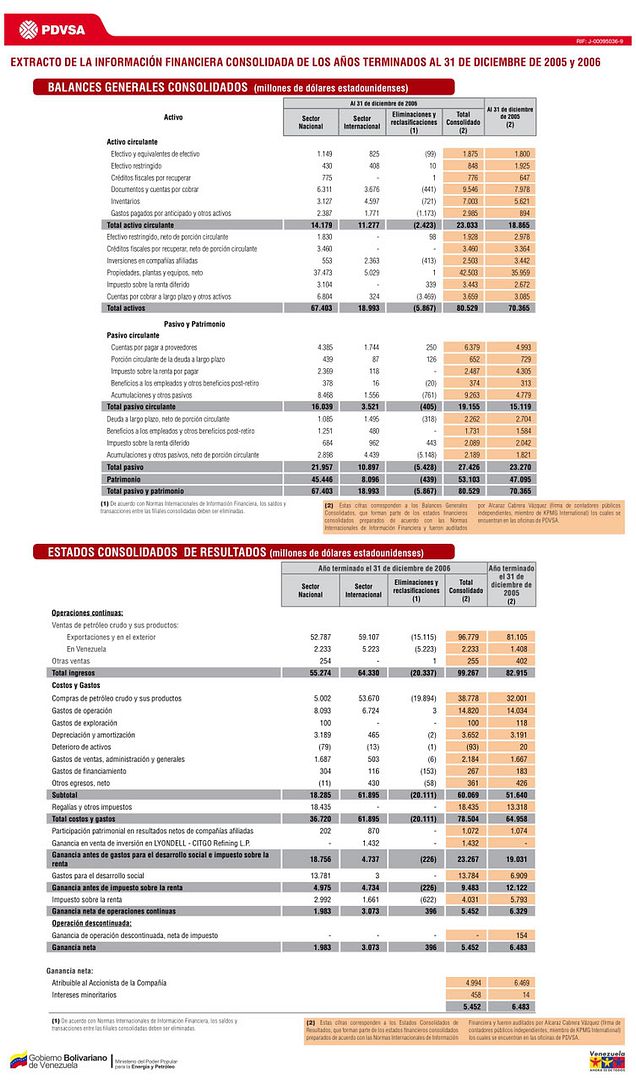

It should be noted that all of PDVSA’s financial statements, both the ones posted on the SEC web site and the ones now referenced on PDVSA’s own web-site are audited by an outside auditing firm which is an affiliate of KPMG. In fact, here is a copy of one with only “basic figures”:

On page one the AUDITED financial statement clearly points out that Venezuelan oil production last year was 3.25 million barrels per day. So it is not just PDVSA “claming” this, its audited financial statements say that is what it is.

Of course some contrarian may say – “but production numbers aren’t audited so maybe they are lying about those”. Yet even if it were true that production numbers weren’t audited it wouldn’t matter. From the financial statement we see that Venezuela got approximately $53 billion in revenue from exporting oil and oil products. Using the knowledge that Venezuelan oil averaged $55 per barrel last year and that there are 365 days in the year we can see that Venezuela had to be exporting approximately 2,600,000 barrels per day. Add in the 650,000 that even Rosenberg acknowledges is consumed domestically and we, very mysteriously, arrive at Venezuela producing 3,250,000 barrels of oil per day.

Will the contrarians now tell us that the auditors don’t audit the money either? If only Ms. Rosenberg had read PDVSA’s financial report and done some elementary arithmetic she could have caught the Venezuelan government telling the truth.

The reality of the situation is that if you don’t believe that Venezuela is producing over 3 MBPD of oil then you really do have a big mystery on your hands, namely where is all the money coming from?

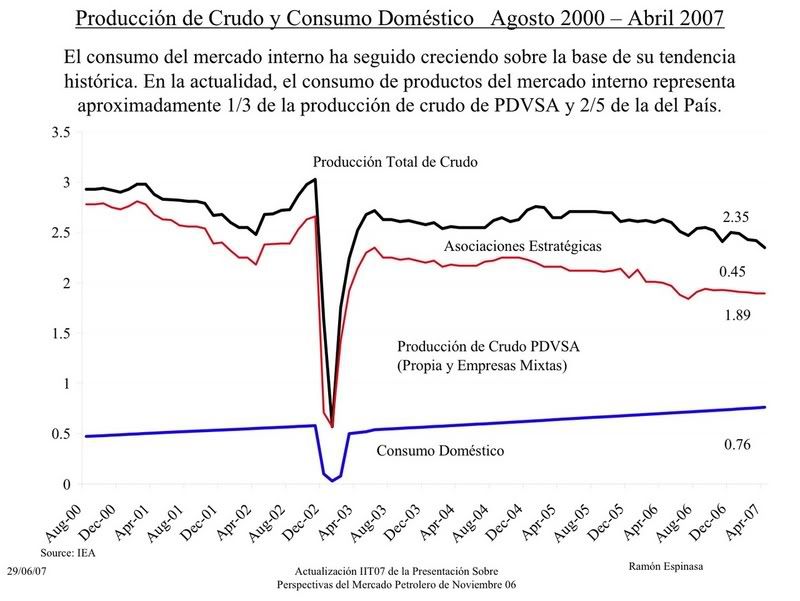

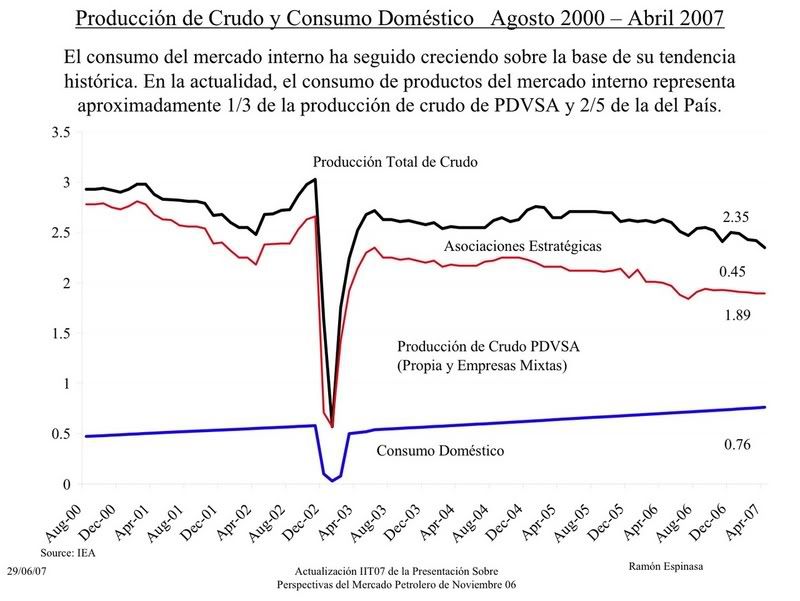

In fact, if she was on the ball she could have picked up on this from Mr. Espinasa’s own reports on Venezuela’s oil industry. You see, he gives numbers showing declining Venezuelan oil production and that match the numbers Ms. Rosenberg uses:

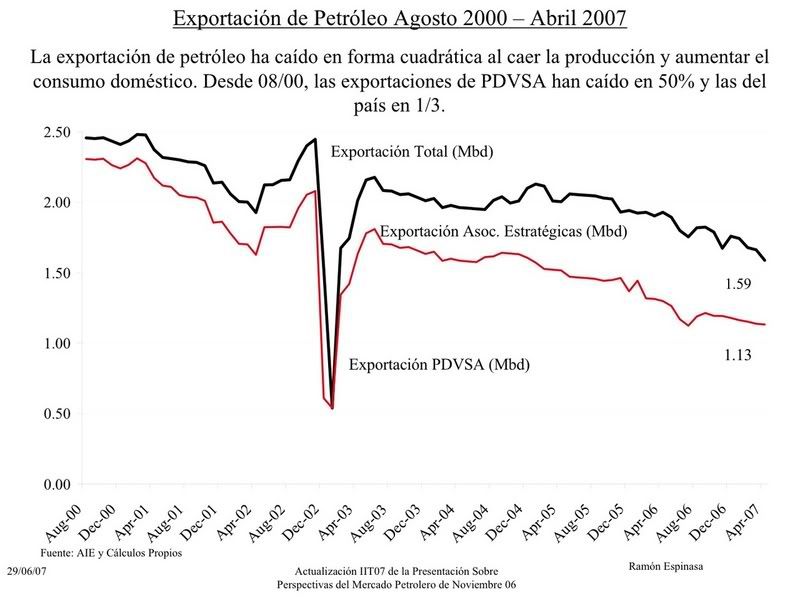

From that it follows that exports have also declined and are only about 1.6 million barrels per day as Espinasa shows in the next chart.

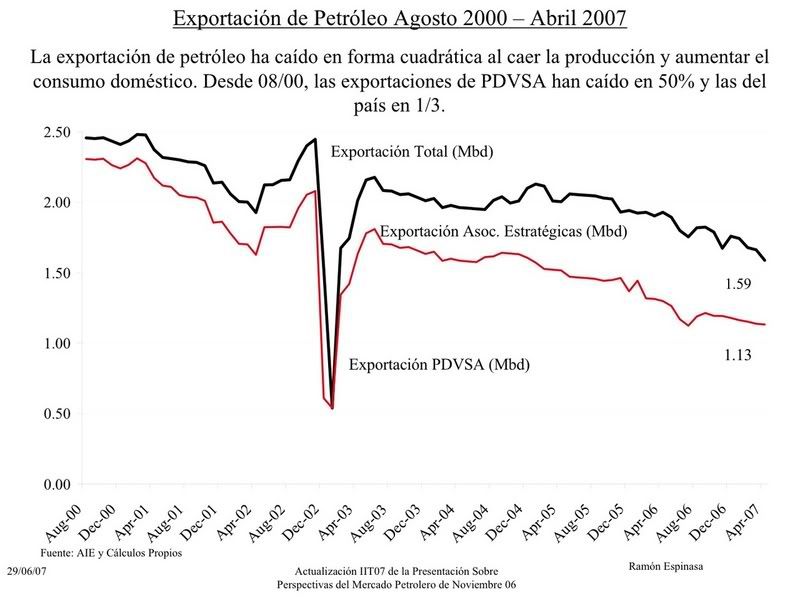

Of course we have no idea where these numbers come from, they certainly aren’t coming from any audited financial statements. But that is not the point as there is a much more fundamental problem with them. Witness the following chart which is two slides later in the very same presentation by Espinasa (the entire presentation can be found here):

In this chart Espinasa readily admits that in 2006 Venezuela exported $60 billion dollars worth of oil (for those of you wonder why it is higher than the $53 billion on PDVSA’s financial statement it is because Espinasa’s numbers include the non-PDVSA portion of the Orinoco Belt production which would not be counted in the PDVSA financial statements – yet another nuance of the Venezuelan oil industry beyond Rosenberg’s grasp).

The reason I show this slide is because it completely blows his earlier slides on production and exports out of the water. A couple of quick calculations will quickly show anyone interested that Venezuela had to export far, far more than 1.6 million barrels and produce far more than 2.4 million barrels to bring in that much money. It really is just simple arithmetic involving nothing more sophisticated than multiplication and division.

So never mind that the Venezuelan numbers are both audited and internally consistent. The numbers the PDVSA doubters present, and that Rosenberg is apparently gullible enough to believe, are not only not audited (in fact I have never once heard how these numbers are come up with) they aren’t even internally consistent. The production and revenue numbers people like Espinasa give can’t possibly be right because they completely contradict each other. Yet Rosenberg is so unquestioning she can’t be bothered to spend a few minutes on a calculator and figure out that her primary source is clearly leading her astray.

The fact that she didn’t read any of the financial statements becomes even more obvious when she says:

It is true that PDVSA took on debt earlier this year and the wisdom of that is debatable. But had she bothered to read any of PDVSA’s financial statements (which can be found here) she would have found out that PDVSA had at least $7 billion in debt early this decade – hardly “very little”.

In fact, she really should have known that the whole reason PDVSA had to file financial statements with the U.S. Security Exchange Commission in the first place was because they had large amounts of debt held by bondholders in the U.S. It was only because under Chavez they paid those debts off that they could stop filing with the SEC after 2004.

I guess it is too late now but knowing that might have prevented her from letting the bald faced lie that they didn’t have any debt before go unchallenged. But repeating other people’s lies is what happens when you don’t do your homework. (BTW, she also repeats the lie that Ramirez said that people who don’t support Chavez can’t work at PDVSA – I guess we can assume she didn’t watch the video of that either even though it can be easily found on YouTube).

Comically, she goes on to claim that Venezuela “once” had a savings fund for oil revenues with $6 billion in it that now only hold $700 million. I guess you could be forgiven if you thought that some previous government saved up money and Chavez then blew the wad. But in reality the “once” was earlier this decade after Chavez boosted oil revenues and paid into it – the fund didn’t exist at all before Chavez and previous governments left him not a single dollar of saved up oil revenues.

Further, the money was spent when the PDVSA managers shut down the oil industry and put the economy in a full blown depression. If you can’t spend the money in that situation, when can you spend it?

Ms. Rosenberg’s indolence and failure to dig out facts aside, the Venezuelan oil industry is doing just fine. Venezuela is producing exactly what it should be to maximize revenues and the revenues themselves are way up, confirming that sticking to OPEC quotas is indeed a wise policy. No one, including Ms. Rosenberg, need cry for PDVSA, it really couldn’t be better as any one who carefully and honestly looks at the facts will see.

Unfortunately, her being distracted by the unfounded allegations about PDVSA sidetracked her from what could have made for a very interesting article – how exactly should Venezuela’s oil income be used. She does correctly note that large oil windfalls often dampen other economic activity – especially manufacturing and exports. Given that Venezuela clearly is suffering from some of those problems a good discussion on that topic would have been very welcome.

Unfortunately, she never returns to that topic. Rather she goes off on a tangent yet again and discusses whether Venezuela would be better off if oil extraction were done by private companies that were then heavily taxed. That is, should Venezuela then let private companies produce the oil rather than having a state owned like PDVSA do it? Personally, I think it is a moot point because PDVSA was nationalized well before Chavez came to office and after a long struggle it is finally now a well run company. If it is not broken, why fix it?

Also, there are possible downsides to allowing private companies control production. First, they aren’t going to do it for free – they are going to want a profit, probably a big profit. In fact in both the Orinoco belt and in older oil fields were they were also allowed in the private oil companies were robbing Venezuela blind. Even if the government is effective in negotiating a very high level of royalties and taxes the companies are going to expect to make a decent profit and that stands in contrast to a state owned model where the government gets all the profits. So it would only make sense economically to allow in private companies if the gains in efficiencies would be greater than the profits that are surrendered to them.

A second, and possibly bigger obstacle to allowing in private firms, is that they are generally not going to be receptive to having to reduce output to stay within OPEC quotas. It is certainly not lost on the Venezuelan government that they have been sued by private companies precisely for cutting production due to OPEC quota reductions.

Lastly, switching to a private oil company model does nothing to solve the very real problems that Ms. Rosenberg noted oil producing countries can have. An overvalued currency, undermining of local industry, graft, and all the other problems of the “petro-state” would still exist.

The reason is those problems have nothing to do with who takes the oil out of the ground. Rather they result from the government controlling all the money. In Rosenberg’s model where private companies extract the oil but the vast majority of the money still goes to the government you would quite likely have all the same problems.

That Ms. Rosenberg missed this point shows she really hasn’t thought much of any of this through clearly. So in fairness to people like Sosa-Pietri and Giusti, let me at least point out that they do claim to have a definitive solution to those problems – giving ownership shares of PDVSA to every Venezuelan citizen so that they receive the oil rents directly rather than having them pass through a potentially corrupt and inefficient government.

Despite a promising beginning where Ms Rosenberg accurately identified some of the pitfalls facing oil producing countries the article proved to be a major disappointment. This again goes back to her just not having gotten straight what the fundamental issues and debates around Venezuelan oil policy have been.

Again, the biggest dispute has always been what Venezuela should with all the oil it sits atop – should it intentionally limit how much oil it produces, in conjunction with OPEC, hoping to maximize revenues by boosting prices, or should they maximize production and maybe if prices do well anyways also have high revenues?

In fact, both schemes have been tried for approximately a decade: the latter for much of the 90s and the former during the entire time Chavez has been in office.

The production maximization experiment went badly as quota busting led to steady declines in prices which in turn greatly reduced revenues and sent the Venezuelan economy into a downward spiral. In contrast, the strategy of working with OPEC to limit production and defend prices has proven spectacularly successful with Venezuelan revenues having increased many times over. As far as I this blogger is concerned that debate is all but over with the defending prices model having proven itself to be vastly superior and more profitable. It is hard to see how any honest person can argue otherwise after the experience of the past 20 years.

The second argument is what should Venezuela do with the oil monies it gets: should it spend them on imports, should it invest them, should it give each citizen a check, or should it save up for a rainy day? This is a very real debate that has yet to be settled. For example, while I certainly consider their oil policy to be a major success I think many of their other macro-economic policies are anything but wise.

Although Rosenberg notes some of the problems Venezuela faces and how important it is for future generations that something be done to develop the rest of the economy she abandons this most important discussion and never returns to it.

We quite possibly get a hint of why when she says of Venezuela: “It has become a rich country of poor people”. That is utterly false. For all its oil Venezuela is still very poor. A couple thousand bucks per person, which is what Venezuela gets from oil in its best years, doesn’t go very far.

Only if a way can be found to leverage Venezuela’s oil riches to bring about comprehensive economic development can the country ever cease to be poor. But Rosenberg fails to discuss at all how this might be done and her article therefore winds up contributing nothing to peoples understanding of Venezuela, its oil industry, and the problems it faces as it struggles to develop.

|

Fortunately for Venezuela there really isn’t much more to this dichotomy than some pretty poor reporting. Case in point is “The perils of Petrocracy” in today’s New Times.

The first problem with the article is it is a fairly large bait and switch. It starts off as if it is going to be about the economic problems that countries with lots of oil run into and whether or not oil is a help or hindrance for their economic development. That is certainly an important topic. Yet the article gets side tracked into a discussion of the current state of the Venezuelan oil industry and never gets back to the subject of oil and development. But more on that later.

Unfortunately even though the article is mainly about the Venezuelan oil industry it doesn’t even prove very informative about that as the author, Tina Rosenberg, clearly failed to do her homework. She doesn’t bother to familiarize herself with all the readily available information on the subject and when she talks to the former overlords of the Venezuelan oil industry – who just maybe have an axe to grind – she doesn’t even know enough to ask the right questions or bring up key facts which might cast doubt on their assertions.

For starters there is this complete misunderstanding of what the dispute over the oil industry is really all about:

In the 1990s, Venezuela’s state oil company was a sleek machine, an excellent exploiter of oil, well fed on its own profits. It floated above society, unmoored from the problems of the average citizen. Today, oil money feeds and educates poor neighborhoods. The purpose of the national oil company is not to produce more oil, but to produce Bolivarian socialism. These are two very different ways to handle a nation’s oil resource. Can either model show poor countries how to convert natural resources into sustained wealth? Few questions in economic policy are more important today.

Here Ms. Rosenberg has completely confused the issues of what Venezuela should do to develop economically – i.e., how should it use the oil revenues that it gets – with the other very hotly debated topic of how Venezuela should maximize it oil income – i.e. how should Venezuela use the abundant oil it has in the ground to generate the greatest amount of income. The dispute over how the state owned oil company, PDVSA, should be used is NOT between pumping more oil or “producing Bolivarian socialism” but between pumping more oil just to have a bigger oil company or pumping less oil to have higher oil prices and hopefully more revenue for Venezuela.

In other words should PDVSA try to become as big as Exxon-Mobil, even if it generates less revenue for the country in the process, or should Venezuela be a good member of the OPEC cartel and restrict oil output to increase the amount of money they get for their oil?

That debate, the REAL debate regarding oil policy, has been going on in Venezuela for 40 years now. Before Chavez came to office those who just wanted to grow PDVSA had power. They were notorious OPEC quota busters (Venezuela was producing 700,000 barrels per day over its quota when Chavez came to office). Their quota busting policies helped push oil prices steadily lower in the 1990s and in turn sent Venezuela’s economy into a tailspin.

So unaware of this is Ms. Rosenberg is she never once mentions either OPEC quotas or the effect that the level of Venezuelan oil production might have on prices. Prices are presumably set only by outside forces that Venezuela has no control over at all and so it doesn’t even merit thinking about or discussing. In this, she accepts, either consciously or unconsciously, the most fundamental tenet of the anti-Chavez former managers of Venezuela’ oil – that as Venezuelan production levels have no impact on prices and prices should therefore be taken as a given, the only logical policy is to maximize the amount of oil produced. That many other Venezuelans thought differently, including the ones who made Venezuela a founding member of OPEC, completely escaped Ms. Rosenberg’s notice.

Chavez himself of course knew all about those debates and was a firm believer in working with OPEC to restrict production, boost prices, and maximize oil revenues, NOT production. Upon coming to office in 1999 he immediately cut Venezuelan output sharply to conform with OPEC quotas and in the process almost tripled oil prices and greatly increased Venezuela’s oil revenues. The old guard PDVSA management never accepted this and almost immediately set about trying to overthrow his government.

That Ms. Rosenberg doesn’t even understand what the heart of the dispute is – should the country maximize oil production or should it maximize oil revenues and its corralarly of should it ignore OPEC quotas or follow them religiously – leads the entire article astray. Moreover, by not appreciating how contentious this debate has been she doesn’t take sufficient care to verify peoples assertions on the what Venezuela’s industry is like.

For example, she clearly swallows the erroneous assertion that Venezuela was a well run oil producing machine before Chavez and is now much less efficient hook, line and sinker. She bases this belief not on any actual analysis but probably on getting most of her information from the PDVSA management that was fired by Chavez.

In reality, before Chavez PDVSA was highly corrupt and it was that corruption which led them to want to maximize production.

In the early 1990s when PDVSA embarked on a course of ignoring OPEC increasing production, profits be damned, it was led by Andres Sosa Pietri. In his book “Petroleo y Poder” (a book that should be read by anyone with even a passing interest in the Venezuelan oil industry but was obviously not read by Ms. Rosenberg) he lays out his beliefs that PDVSA should be run free of any control by the state, that production should be maximized, and that Venezuela should leave OPEC.

He also, in a bout of honesty, notes that his family owned the Constructora Nacional de Valvulas (the National Valve Fabricator) which made all the pumps and valves used by PDVSA as it expanded production. This is a stunning conflict of interest (and it should be noted that the shareholders of a private corporation would never tolerate such a clear conflict of interests) and makes it more than obvious why he would want to maximize production – the country might make less money but all the new PDVSA investment would, and did, make his family wealthy.

Later the company was run by Luis Giusti. He believed in ignoring OPEC and maximizing production just as much as Sosa Pietri did. He also believed in opening up Venezuelan oil exploitation to private firms whose long term, favorable contracts would, as Bernard Mommer (another key observer of the Venezuelan oil industry who Ms. Rosenberg has apparently never hear of and never read) noted, help force Venezuela to leave OPEC.

Mr. Giusti was no less self-serving in his policies than was Sosa Pietri. During his tenure most of PDVSA’s finance and administrative functions were spun off into a private for profit company called Intesa which Mr. Giusti had direct financial interests. Of course, the bigger PDVSA became the more profits there would be for Intesa and for Mr. Giusti himself. So once again we see that PDVSA’s policy of hyper growth most likely grew out of a desire not to help Venezuela but rather to help the top management of the company enrich itself.

So this morass of insider dealing and corruption is what we are supposed to believe was a “sleek machine” and an “excellent exploiter of oil”? The reality is this quota busting, production maximizing company only made its management wealthy while the revenues for the country continually shrank.

Ms. Rosenberg accepts much of the rest of the old PDVSA management’s propoganda. For example, while noting that Citgo may have been used to move oil profits out of Venezuela through transfer pricing (for a discussion of how that worked see Mommer’s article Subervise Oil) she then gushes that both the Citgo purchase and the opening up of production of the heavy oils in the Orinoco Belt were “brilliant business decisions”!

Let’s see how “brilliant” these business decisions were. First, Citgo was purchased without bothering to negotiate a double taxation treaty with the U.S.. This was then used as an excuse for Citgo never to pay any dividends to Venezuela and in fact prior to Chavez coming to office Citgo never paid any. So Venezuela had a multi-billion dollar investment which was not giving it any profits. It is hard for me to see the “brilliance” of that.

Rosenberg then buys into the spurious argument that Citgo refineries would help assure a market for Venezuelan oil. She is apparently unaware that many of the Citgo refineries, and other refineries that Venezuela bought in places like Germany, have never actually refined any Venezuelan oil.

Worse still, this betrays a lack of understanding of basic economics. If Citgo refineries were somehow specially suited to refine Venezuelan oil, which some of them are, they would be buying Venezuelan oil no matter who owned them. In fact, Venezuela recently sold off one of its Citgo refineries in the U.S (one that cost Venezuela $750 million in losses by being forced to sell it under priced oil) and guess what? - it still buys its oil from Venezuela. Venezuela no more needs to own Citgo to sell its oil in the United States than Sony needs to own Best Buy or Circuit City in order to sell its televisions in the U.S.

The Orinoco Belt oil production, which was ramped up to 600,000 barrels of oil per day was the other half of this “brilliant” decision. Yet it only appears brilliant to Rosenberg because she completely ignores the issue of OPEC quotas. If there were no quotas and if Venezuelan output had no effect on prices then maybe having this additional oil revenue would make sense.

However, Venezuela does have an OPEC quota which limits what it can produce. For that reason this Orinoco oil, which is expensive to produce and fetches a lower price on world markets making its profit margin much lower then other Venezuelan oils, displaces other oil. That is, if Venezuela’s quota is 3 million barrels and the Orinoco oil is 600,000 then they have to cut back their other, more profitable production, back to 2.4 million barrels. No normal person would view cutting back on the production of more profitable oil to make way for LESS profitable oil a “brilliant business decision”.

Of course, the real brilliance of the decision from the perspective of people like Sosa Pietri and Giusti was that turning over oil production to private companies would force Venezuela out of OPEC as private companies would never agree to cut their output to stay within quotas. In fact, the co-owner of the Citgo refinery that Venezuela just sold, Lyondell, sued Venezuela in 2002 for cutting back its oil allotment due to OPEC quotas!! If Ms. Rosenberg had bothered to read Sosa-Pietri’s and Giusti’s writings on these subjects she would have known this. But once again she is so unaware of what the issues are she is incapable of even asking the right questions and categorizes as “brilliant” decisions which in fact were disastrous for Venezuelan.

Rosenberg then veers into talking about how “PDVSA” is in trouble”. According to Rosenberg one prime example of “trouble” is “the mystery of the missing drilling rigs”. Venezuelan oil production is falling, she claims, because Venezuela supposedly does not have enough drilling rigs to drill for oil and maintain production which naturally declines as old wells run dry.

To analyze this mystery we fortunately have at our disposal a chart of oil rig numbers in Venezuela prepared by one of Rosenberg’s main sources, the anti-Chavez former PDVSA economist Ramon Espinasa:

The text on this chart says that the current number of rigs is insufficient to maintain a production level of 3 million barrels of oil per day. Yet the numbers in the graph itself show that claim to be false. Looking at it we see that the current number of drilling rigs is equal to or greater than any time except the period between 1995 and 1998. From 1995 to 1998 Venezuela was very rapidly expanding oil production (ie not just maintaining production but increasing it by about 200,000 barrels of daily production every year) to well over three million barrels per day. Given that Venezuela is not currently expanding production (because it has to stay within its OPEC quota) it does not need that number of rigs.

However note that from 1999 to 2002, when the country was simply maintaining production and not expanding it, the number of rigs was actually somewhat LESS than it is today. With around 80 rigs Venezuela managed to keep production levels of around 3 MBPD from 1999 to 2002 so why should that number of rigs all of the sudden be inadequate? The fact is, comparing the number of rigs to what Venezuela’s needs are we see that today’s number of rigs is perfectly adequate to maintain production levels.

Should Venezuela want to significantly expand production, as its long term business plan calls for, it would need more rigs, but given OPEC quotas that is not likely to happen any time soon.

So what we see is the only thing mysterious here is why Ms. Ronsenberg hasn’t better informed herself on these issues and even looked closely at the number presented by her favored sources before giving what is clearly an erroneous analysis.

Continuing on with her “PDVSA is in trouble” theme she then quotes one analyst as saying PDVSA production has been going down for the past couple of years – presumably because of mismanagement and missing oil rigs! Of course, that Venezuela might have intentionally reduced its production to meet cuts in its OPEC quotas over the past two years completely is completely beyond her. Yet that is precisely what happened. Once again, the fact that she barely seems to realize that OPEC exists and what Venezuela’s relationship with it is makes it almost impossible for her to get much of anything right in this article.

As Ms. Rosenberg clearly wasn’t doing any independent verification of facts and was relying on the fired PDVSA managers for most of her information I had to wonder when she was going to get to the biggest two canards surrounding the Venezuelan oil industry – that PDVSA is no longer transparent and that its oil production is much less than what it says it is. I didn’t have to wait long.

First she starts with “[PDVSA] has become less and less transparent”. She goes on to say:

The company used to publish a standard annual report, but after 2004 it stopped filing its annual reports to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. In recent years it has released only a page or two of basic figures, with no breakdowns or auditors’ notes. When Pdvsa does release information, some of it is of questionable credibility. Even the most fundamental operational fact — how much oil Venezuela produces — is subject to debate. In 1997, Venezuela produced 3.3 million barrels per day of crude oil. Today, Pdvsa claims the country produces the same amount, but independent sources, including OPEC, say that figure is too high; OPEC puts Venezuela’s production at 2.4 million barrels a day last year.

One thing I’ve always wondered about this whole transparency discussion is if a company publishes financial statements and no one bothers to read them does it really do much for transparency? The reason I pose that question is because, as will become clear shortly, Ms. Rosenberg obviously did not read any of PDVSA’s financial statements.

It should be noted that all of PDVSA’s financial statements, both the ones posted on the SEC web site and the ones now referenced on PDVSA’s own web-site are audited by an outside auditing firm which is an affiliate of KPMG. In fact, here is a copy of one with only “basic figures”:

On page one the AUDITED financial statement clearly points out that Venezuelan oil production last year was 3.25 million barrels per day. So it is not just PDVSA “claming” this, its audited financial statements say that is what it is.

Of course some contrarian may say – “but production numbers aren’t audited so maybe they are lying about those”. Yet even if it were true that production numbers weren’t audited it wouldn’t matter. From the financial statement we see that Venezuela got approximately $53 billion in revenue from exporting oil and oil products. Using the knowledge that Venezuelan oil averaged $55 per barrel last year and that there are 365 days in the year we can see that Venezuela had to be exporting approximately 2,600,000 barrels per day. Add in the 650,000 that even Rosenberg acknowledges is consumed domestically and we, very mysteriously, arrive at Venezuela producing 3,250,000 barrels of oil per day.

Will the contrarians now tell us that the auditors don’t audit the money either? If only Ms. Rosenberg had read PDVSA’s financial report and done some elementary arithmetic she could have caught the Venezuelan government telling the truth.

The reality of the situation is that if you don’t believe that Venezuela is producing over 3 MBPD of oil then you really do have a big mystery on your hands, namely where is all the money coming from?

In fact, if she was on the ball she could have picked up on this from Mr. Espinasa’s own reports on Venezuela’s oil industry. You see, he gives numbers showing declining Venezuelan oil production and that match the numbers Ms. Rosenberg uses:

From that it follows that exports have also declined and are only about 1.6 million barrels per day as Espinasa shows in the next chart.

Of course we have no idea where these numbers come from, they certainly aren’t coming from any audited financial statements. But that is not the point as there is a much more fundamental problem with them. Witness the following chart which is two slides later in the very same presentation by Espinasa (the entire presentation can be found here):

In this chart Espinasa readily admits that in 2006 Venezuela exported $60 billion dollars worth of oil (for those of you wonder why it is higher than the $53 billion on PDVSA’s financial statement it is because Espinasa’s numbers include the non-PDVSA portion of the Orinoco Belt production which would not be counted in the PDVSA financial statements – yet another nuance of the Venezuelan oil industry beyond Rosenberg’s grasp).

The reason I show this slide is because it completely blows his earlier slides on production and exports out of the water. A couple of quick calculations will quickly show anyone interested that Venezuela had to export far, far more than 1.6 million barrels and produce far more than 2.4 million barrels to bring in that much money. It really is just simple arithmetic involving nothing more sophisticated than multiplication and division.

So never mind that the Venezuelan numbers are both audited and internally consistent. The numbers the PDVSA doubters present, and that Rosenberg is apparently gullible enough to believe, are not only not audited (in fact I have never once heard how these numbers are come up with) they aren’t even internally consistent. The production and revenue numbers people like Espinasa give can’t possibly be right because they completely contradict each other. Yet Rosenberg is so unquestioning she can’t be bothered to spend a few minutes on a calculator and figure out that her primary source is clearly leading her astray.

The fact that she didn’t read any of the financial statements becomes even more obvious when she says:

Pdvsa is also taking on debt. The company had very little debt until 2006, but this year it has borrowed $12.5 billion. While raising cash through debt offerings can be fiscally sound, and many companies do so, critics contend that Pdvsa is issuing bonds for the wrong reasons. “Their debts are low, but they didn’t have any before,” says José Guerra, formerly chief of the research department of the Central Bank, who left in disagreement about Chávez’s economic policies. “Other oil countries are getting rid of debt. And what is the debt going for? Their spending on exploration is almost nothing. They are taking on debt to have a party.”

It is true that PDVSA took on debt earlier this year and the wisdom of that is debatable. But had she bothered to read any of PDVSA’s financial statements (which can be found here) she would have found out that PDVSA had at least $7 billion in debt early this decade – hardly “very little”.

In fact, she really should have known that the whole reason PDVSA had to file financial statements with the U.S. Security Exchange Commission in the first place was because they had large amounts of debt held by bondholders in the U.S. It was only because under Chavez they paid those debts off that they could stop filing with the SEC after 2004.

I guess it is too late now but knowing that might have prevented her from letting the bald faced lie that they didn’t have any debt before go unchallenged. But repeating other people’s lies is what happens when you don’t do your homework. (BTW, she also repeats the lie that Ramirez said that people who don’t support Chavez can’t work at PDVSA – I guess we can assume she didn’t watch the video of that either even though it can be easily found on YouTube).

Comically, she goes on to claim that Venezuela “once” had a savings fund for oil revenues with $6 billion in it that now only hold $700 million. I guess you could be forgiven if you thought that some previous government saved up money and Chavez then blew the wad. But in reality the “once” was earlier this decade after Chavez boosted oil revenues and paid into it – the fund didn’t exist at all before Chavez and previous governments left him not a single dollar of saved up oil revenues.

Further, the money was spent when the PDVSA managers shut down the oil industry and put the economy in a full blown depression. If you can’t spend the money in that situation, when can you spend it?

Ms. Rosenberg’s indolence and failure to dig out facts aside, the Venezuelan oil industry is doing just fine. Venezuela is producing exactly what it should be to maximize revenues and the revenues themselves are way up, confirming that sticking to OPEC quotas is indeed a wise policy. No one, including Ms. Rosenberg, need cry for PDVSA, it really couldn’t be better as any one who carefully and honestly looks at the facts will see.

Unfortunately, her being distracted by the unfounded allegations about PDVSA sidetracked her from what could have made for a very interesting article – how exactly should Venezuela’s oil income be used. She does correctly note that large oil windfalls often dampen other economic activity – especially manufacturing and exports. Given that Venezuela clearly is suffering from some of those problems a good discussion on that topic would have been very welcome.

Unfortunately, she never returns to that topic. Rather she goes off on a tangent yet again and discusses whether Venezuela would be better off if oil extraction were done by private companies that were then heavily taxed. That is, should Venezuela then let private companies produce the oil rather than having a state owned like PDVSA do it? Personally, I think it is a moot point because PDVSA was nationalized well before Chavez came to office and after a long struggle it is finally now a well run company. If it is not broken, why fix it?

Also, there are possible downsides to allowing private companies control production. First, they aren’t going to do it for free – they are going to want a profit, probably a big profit. In fact in both the Orinoco belt and in older oil fields were they were also allowed in the private oil companies were robbing Venezuela blind. Even if the government is effective in negotiating a very high level of royalties and taxes the companies are going to expect to make a decent profit and that stands in contrast to a state owned model where the government gets all the profits. So it would only make sense economically to allow in private companies if the gains in efficiencies would be greater than the profits that are surrendered to them.

A second, and possibly bigger obstacle to allowing in private firms, is that they are generally not going to be receptive to having to reduce output to stay within OPEC quotas. It is certainly not lost on the Venezuelan government that they have been sued by private companies precisely for cutting production due to OPEC quota reductions.

Lastly, switching to a private oil company model does nothing to solve the very real problems that Ms. Rosenberg noted oil producing countries can have. An overvalued currency, undermining of local industry, graft, and all the other problems of the “petro-state” would still exist.

The reason is those problems have nothing to do with who takes the oil out of the ground. Rather they result from the government controlling all the money. In Rosenberg’s model where private companies extract the oil but the vast majority of the money still goes to the government you would quite likely have all the same problems.

That Ms. Rosenberg missed this point shows she really hasn’t thought much of any of this through clearly. So in fairness to people like Sosa-Pietri and Giusti, let me at least point out that they do claim to have a definitive solution to those problems – giving ownership shares of PDVSA to every Venezuelan citizen so that they receive the oil rents directly rather than having them pass through a potentially corrupt and inefficient government.

Despite a promising beginning where Ms Rosenberg accurately identified some of the pitfalls facing oil producing countries the article proved to be a major disappointment. This again goes back to her just not having gotten straight what the fundamental issues and debates around Venezuelan oil policy have been.

Again, the biggest dispute has always been what Venezuela should with all the oil it sits atop – should it intentionally limit how much oil it produces, in conjunction with OPEC, hoping to maximize revenues by boosting prices, or should they maximize production and maybe if prices do well anyways also have high revenues?

In fact, both schemes have been tried for approximately a decade: the latter for much of the 90s and the former during the entire time Chavez has been in office.

The production maximization experiment went badly as quota busting led to steady declines in prices which in turn greatly reduced revenues and sent the Venezuelan economy into a downward spiral. In contrast, the strategy of working with OPEC to limit production and defend prices has proven spectacularly successful with Venezuelan revenues having increased many times over. As far as I this blogger is concerned that debate is all but over with the defending prices model having proven itself to be vastly superior and more profitable. It is hard to see how any honest person can argue otherwise after the experience of the past 20 years.

The second argument is what should Venezuela do with the oil monies it gets: should it spend them on imports, should it invest them, should it give each citizen a check, or should it save up for a rainy day? This is a very real debate that has yet to be settled. For example, while I certainly consider their oil policy to be a major success I think many of their other macro-economic policies are anything but wise.

Although Rosenberg notes some of the problems Venezuela faces and how important it is for future generations that something be done to develop the rest of the economy she abandons this most important discussion and never returns to it.

We quite possibly get a hint of why when she says of Venezuela: “It has become a rich country of poor people”. That is utterly false. For all its oil Venezuela is still very poor. A couple thousand bucks per person, which is what Venezuela gets from oil in its best years, doesn’t go very far.

Only if a way can be found to leverage Venezuela’s oil riches to bring about comprehensive economic development can the country ever cease to be poor. But Rosenberg fails to discuss at all how this might be done and her article therefore winds up contributing nothing to peoples understanding of Venezuela, its oil industry, and the problems it faces as it struggles to develop.

|