Saturday, December 22, 2007

Getting back to basics

In the preceding posts I have pointed out some of the wasteful subsidies, primarily benefiting the wealthier segments of Venezuelan society, that the Venezuelan government can no longer afford and needs to start looking for ways to limit.

One of the main objections to some of my proposed reforms is that they may make sense economically but are not viable politically. That is, they would prompt a strong reaction not only among the traditional opponents of Chavez but also possibly among his political base of the poor and working class.

This is certainly an important consideration. After all Venezuela is a full blown democracy with full freedom of expression and a strident oppositional media. Unlike South Korea and China where public opinion was not a concern because opposition was/is simply repressed the Venezuelan government does have to concern itself with public opinion and poll numbers.

For that reason Venezuela's policy making decisions are more complex - not only must the policies be right economically, they must also be "right" politically. Failure in either respect is untenable in the medium to long term either because they will in the first case fail economically or cause the government to be voted out of office in the second case.

In making my recommendations for new policies I did try to take into account the politics of these subsidies. In point of fact, what made these subsidies obvious targets for cuts in my mind was the fact that they overwhelmingly favor the more well of segments of the Venezuelan population that have been strong opponents of Chavez pretty much all along. I therefore viewed the elimination of these subsidies as both economically important and politically viable, if not advantageous.

Still, many readers seem to not be convinced of that. Part of the reason is I believe is that with all the talk of economic boom and a consumption binge it is easy for people to forget how most Venezuelans live.

To help refresh peoples memories I would like to revisit some slides giving the socio-economic breakdown of Venezuelan society, how much the different groups earn, what they tend to consume, and how large they are. These slides were first published a couple of years ago so they are obviously a little dated given the recent boom, but not by much and the portrait of Venezuelan society and peoples standard of living is still largely accurate. Also, after we finish reviewing each slide we will see precisely how these groupings have changed.

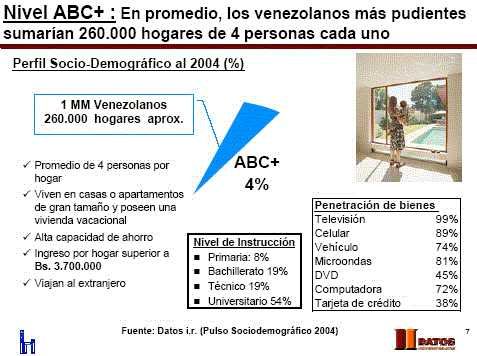

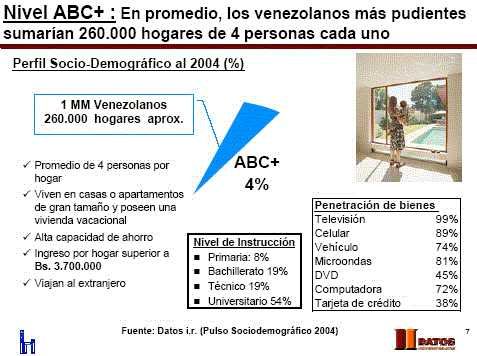

The first slide shows those at the top of the heap in Venezuela - social classes A, B and the top part of C:

This high income group comprises about 1 million people and they have relatively high incomes, good living conditions, the ability to save money and and also have high levels of education. Looking at what they own they not only have the things virtually all Venezuelans seem to have like televisions and cell phones but they also have luxury items like micro-wave ovens (81%), computers (72%), DVDs (45%), and automobiles (74%). Further, a sizable number of them (38%) have credit cards.

So one can see that they very heavily consume items that in Venezuela are almost entirely imported. Further, as the slide indicates they travel outside of Venezuela, a luxury enjoyed by very few Venezuelans. These facts will be significant when we revisit the specific subsidies the government is giving.

Next we move down the social scale to the middle/lower middle class (known as C- in Venezuela):

This group is significantly larger, consisting of 15% of the population or 4 million people at the time. While its income is less than half of the previous group it still has a lot of expensive imported consumer items - 60% have cars, 65% have microwaves, 49% DVDs, 51% computers, and a still sizable 27% have credit cards. While no reference is made to it, probably some of these people can occasionally take trips abroad.

Clearly this group is going to be favored by the same sort of policies that favored by the top income group, just to a lesser degree.

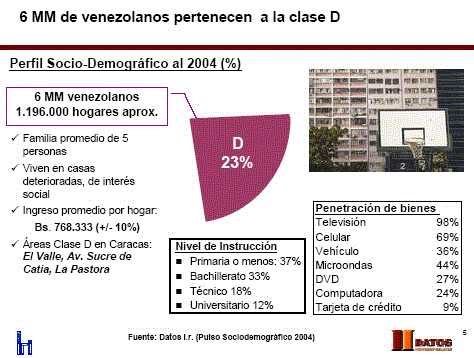

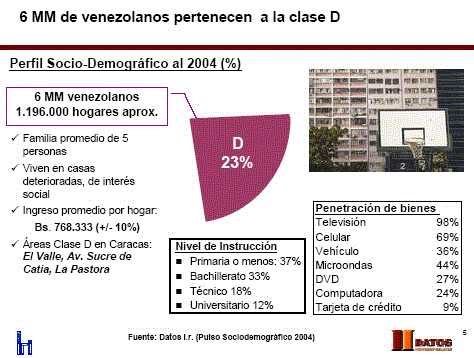

Next we move out of the middle class and down to the working class or social class D:

This group made up 23% percent of the Venezuelan population or 6 million people (we will see shortly how those numbers have changed). This group is not only much bigger than the previous ones but it is also much less affluent. Rather than living in decent, if not very nice, housing as the previous groups do these people tend to live in run down private homes or public housing. Further, while they still generally have TVs and cell phone, only a minority of them own other imported consumer goods - 44% have microwaves, 27% DVDs, 24% have computers, and only 36% have their own cars. And only a very small minority have credit cards.

Further, although it isn't explicitly stated it is safe to assume people in this social class do not travel abroad at all. Not only could they never afford it, they would never be given a visa to entry any developed countries like the United States, Canada or the European Union.

Next we come to the final group - the poor and working poor, social class E:

This has for a long time been the socio-economic class of most Venezuelans encompassing 58% of the population and more than 15 million people.

These are people who are doing little more than getting by and who populate the huge hillside slums of Caracas and the other very numerous poor areas throughout Venezuela. They may get enough to eat and have clothes on their back (though significant portion don't even have those things) but they have very little in the way of consumer goods: only 18% have microwaves, 11% DVDs, 8% have computers, and only 18% have their own cars. A mere three percent have credit cards. And, of course, these people are not hopping on airplanes and traveling overseas.

Although we will go into greater detail shortly we can see here a fairly clear dividing line - the first two groups ABC, and C- are very big consumers of imported items and account for just about all travel abroad. Further, they are the only groups where the majority of people own private automobiles. The latter two groups, D and E, which together represent the vast majority of the population, consume far fewer imported items, don't travel abroad and generally don't have cars.

It is therefore clear that the first group makes heavy use of dollars via imports and travel and also makes heavy use of free gasoline via the cars they own so I will call them heavy consumers. The second group consumes far fewer imported items and hence is much less dependent on access to dollars. Further, they use relatively little of Venezuela's free gasoline as they generally don't own automobiles. I will therefore call them light consumers.

There are two more slides that we should look at before drawing any conclusions.

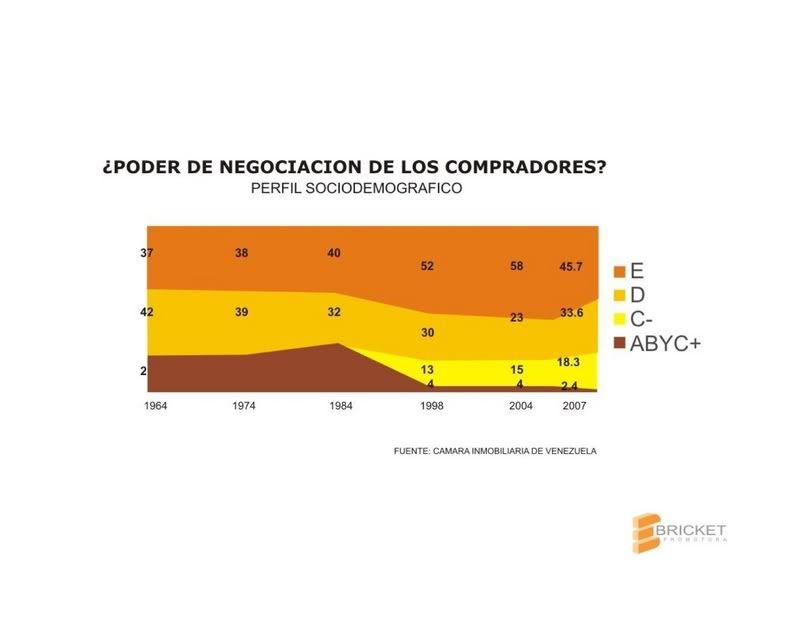

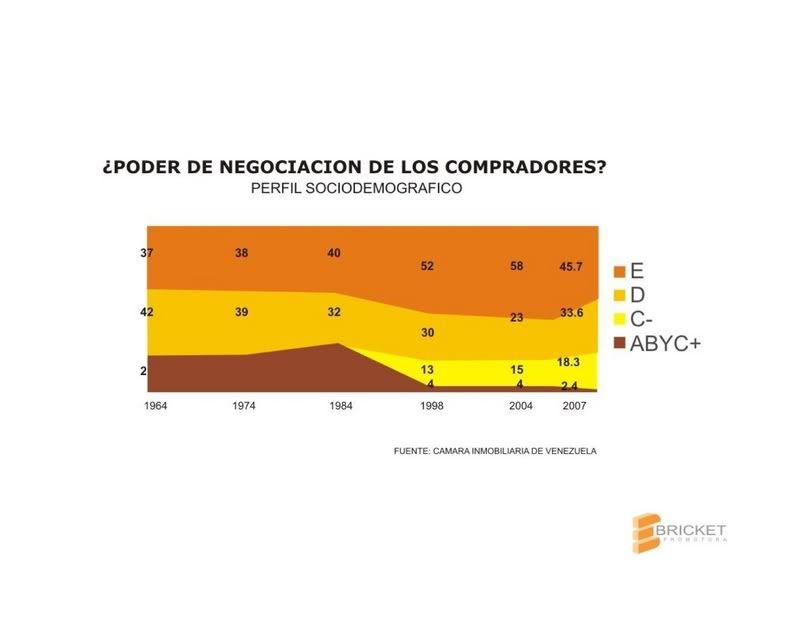

The first shows how the size of these socio-economic groups has changed recently:

Note that the heavy consumers, groups ABC+ and C-, didn't change much between 2004 and 2007. In 2004 they totaled 19% of the population and this year they increased to 20.7%. Clearly, these heavy consumers are still a small minority, barely more than a fifth of the total population.

Next note that the total number of light consumers, groups D and E, also didn't change much. In 2004 they totaled 81% and currently they constitute 79.3% of the population. The main change was within this grouping where a significant number of people who had been poor or working poor were able to move up to the working class.

Still the dividing line between heavy consumers and light consumers is pretty clear and unchanged - about 20% are heavy consumers and 80% are light consumers.

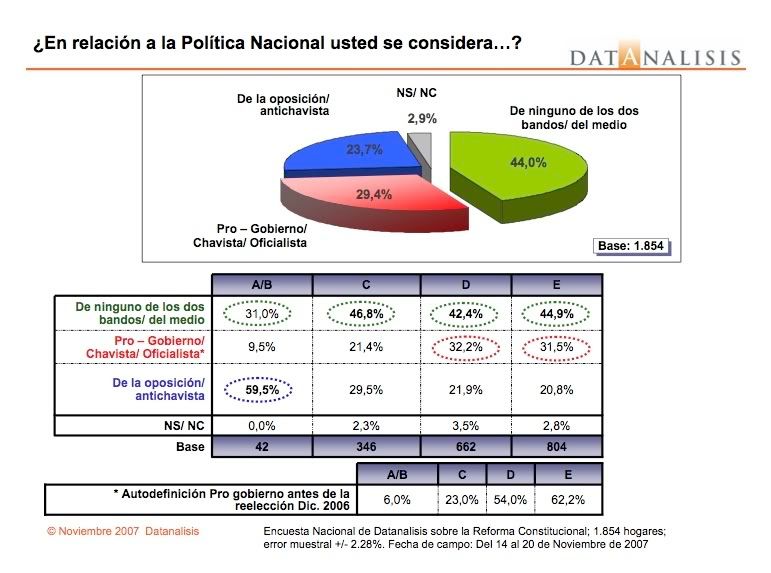

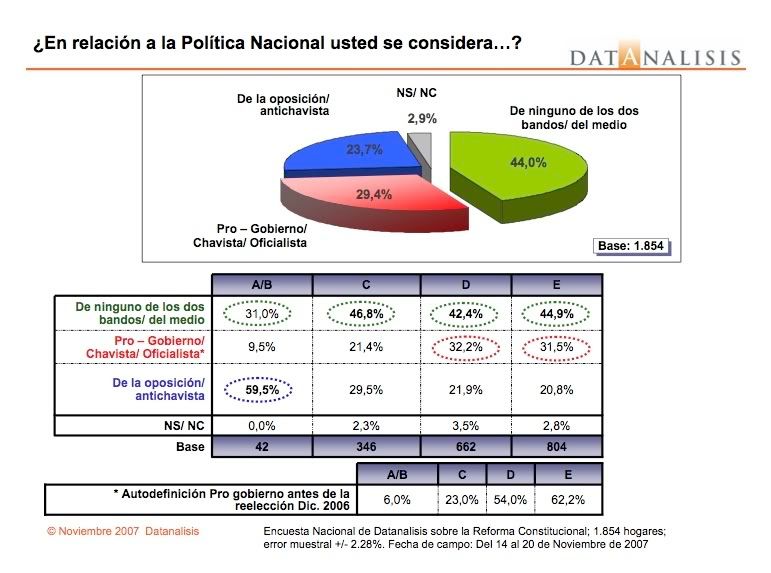

Finally lets look at their political tendencies:

This polling information from Datanalisis shows that the greatest level of support for the government is among classes D and E (the red circles) while the greatest opposition to the government is among the high income A and B groups (the blue circle).

If that data was maybe a little muddled by controversial constitutional reform proposal it can be seen much more clearly at the bottom where the data from before last years presidential election was given. There we clearly see that only a very small portion of the heavy consumers (A,B and C classes) support Chavez whereas large majority of the light consumers support Chavez.

In summary, heavy consumers are clearly anti-Chavez and constitute the oppositions political base while light consumers heavily favor Chavez and are his political base. Therefore, anything that were to adversely effect the light consumers would probably be political suicide for Chavez while policies that adversely effect heavy consumers would cause him little political harm.

With this in mind lets review some of the proposals from my last two posts.

In the first post it was pointed out half a billion dollars were being sent overseas to family members, another half a billion was spent on airlines, and a whopping $4.2 billion was spent for dollar transactions on credit cards. I stated that it would be wise for the government to either eliminate or curtail these expenditures. From an economic point of view it would make a lot of sense as it could save the country billions of dollars that could be better spent other items or simply saved.

But would restricting these expenses be politically viable? Well the dollars spent on airlines and sent overseas to relatives would clearly only effect the heavy consumers - they are the only ones who travel abroad. Further, restricting the use of credit cards for dollar purchases would only effect the upper classes also. Remember, 38% of classes A,B and C- and 27% of class C- have credit cards while only 9% of social class D have them and a minuscule 3% of social class E have them.

From this is should be very clear, that reducing the dollars allowed for overseas travel and dollar purchases with credit cards should NOT present a political problem for Chavez as those measure will almost exclusively impact those who don't support him in the first place.

So from a economic AND political viewpoint it would seem a no-brainer to go ahead with these measures.

In the following post I proposed raising the price of gasoline for private automobiles as a way of saving the Venezuelan government billions of more dollars. Also recall, I proposed continuing the same discounted prices for fuel used by buses and trucks so that this would only impact those with their own cars.

Looking at the data above it is clear this would impact the heavy consumers much more than the light consumers, but the divide isn't as clear as it was with overseas travel and credit cards.

Note that automobile ownership rates for heavy consumers are 74% for classes ABC- and 60% for class C-. Clearly raising gasoline prices will hit heavy consumers hard and they are likely to protest against it. But given that very few of them support Chavez in the first place, 6% of the former and 23% of the latter, that shouldn't impact Chavez's political fortunes.

By way of contrast, only a minority of light consumers have cars, 36% of social class D and 18% of class E. Most people in this group don't have cars.

Still, in contrast to the previous case where almost no light consumers travel abroad or have credit cards, in this case a significant number of them do have cars. That means that some of them WOULD be hard hit by a gasoline price increase and there would be at least some political repercussions for Chavez in carrying out this measure.

However, the losses through via making gasoline essentially free are huge (at least $20 billion!!) and even recovering a portion of those losses is simply too big a bonus for the country for it NOT to be done.

All this said, the cost saving measures that have been proposed clearly are politically viable as they would primarily impact those opposing Chavez and leave his political base untouched. However, the impact is uneven with a gasoline price hike being more politically costly to Chavez than the other measures.

That suggests one possible course of action. The government could first restrict the dollars for travel abroad and credit card purchases. By doing so they could save at least $2.5 billion dollars and possibly as much as $5 billion. These funds could then be dedicated to measures which would show immediate benefits to the population.

For example, this year little more than $2 billion was spent on food imports. If the money saved from restricting travel and credit cards were dedicated exclusively to food purchases the government could easily double or even triple the amount of food it brings in and sells through Mercal. Doing this would help solve a very immediate problem effecting people and buy it much political good will.

Then 6 months to a year after doing that the government could implement the more painful measure of raising gasoline prices. By then the government should have earned enough good will through its previous measure to withstand any political fallout from this reform. These savings, which as we saw could be up to $6 billion dollars annually, could then be dedicated to public works and industrialization projects which would also show benefits to the public over the longer term.

Of course, this is only one possible way of doing things and the government could choose other options and timing. But the central point is clear - these necessary economic reforms ARE politically viable and could even boost Chavez's political standing if done properly. Political timidity and fear should NOT be used as an excuse not to pursue these type of necessary reforms.

Lets also be clear about one further point. The Venezuelan government is NOT facing any kind of immediate economic crisis. The economy has been growing very rapidly in recent years, peoples standard of living has been increasing, and most people are happy with the state of the economy. This is likely to continue for at least the next year or two.

However, and this is a huge however, it is just as clear that there are problems which are getting worse and will continue to get worse over time - an overvalued currency, stagnant non-oil exports, a unproductive and unsustainable consumption binge, etc. It is probable that these problems will become a crisis over the longer term if not addressed soon. This means the Venezuelan government has two options:

A) deal with the problems now while they are still relatively small, the solutions won't be too politically costly, and their are no major elections for a number of years

or

B) ignore the problems, face a significant economic crisis in a few years if oil prices decline or even level off, and face this crisis right when Chavez faces the possibility of being recalled or the National Assembly is up for re-election.

Which do you think is better, not only from an economic point of view but also from a political perspective?

If you were Chavez, which option would you choose?

|

One of the main objections to some of my proposed reforms is that they may make sense economically but are not viable politically. That is, they would prompt a strong reaction not only among the traditional opponents of Chavez but also possibly among his political base of the poor and working class.

This is certainly an important consideration. After all Venezuela is a full blown democracy with full freedom of expression and a strident oppositional media. Unlike South Korea and China where public opinion was not a concern because opposition was/is simply repressed the Venezuelan government does have to concern itself with public opinion and poll numbers.

For that reason Venezuela's policy making decisions are more complex - not only must the policies be right economically, they must also be "right" politically. Failure in either respect is untenable in the medium to long term either because they will in the first case fail economically or cause the government to be voted out of office in the second case.

In making my recommendations for new policies I did try to take into account the politics of these subsidies. In point of fact, what made these subsidies obvious targets for cuts in my mind was the fact that they overwhelmingly favor the more well of segments of the Venezuelan population that have been strong opponents of Chavez pretty much all along. I therefore viewed the elimination of these subsidies as both economically important and politically viable, if not advantageous.

Still, many readers seem to not be convinced of that. Part of the reason is I believe is that with all the talk of economic boom and a consumption binge it is easy for people to forget how most Venezuelans live.

To help refresh peoples memories I would like to revisit some slides giving the socio-economic breakdown of Venezuelan society, how much the different groups earn, what they tend to consume, and how large they are. These slides were first published a couple of years ago so they are obviously a little dated given the recent boom, but not by much and the portrait of Venezuelan society and peoples standard of living is still largely accurate. Also, after we finish reviewing each slide we will see precisely how these groupings have changed.

The first slide shows those at the top of the heap in Venezuela - social classes A, B and the top part of C:

This high income group comprises about 1 million people and they have relatively high incomes, good living conditions, the ability to save money and and also have high levels of education. Looking at what they own they not only have the things virtually all Venezuelans seem to have like televisions and cell phones but they also have luxury items like micro-wave ovens (81%), computers (72%), DVDs (45%), and automobiles (74%). Further, a sizable number of them (38%) have credit cards.

So one can see that they very heavily consume items that in Venezuela are almost entirely imported. Further, as the slide indicates they travel outside of Venezuela, a luxury enjoyed by very few Venezuelans. These facts will be significant when we revisit the specific subsidies the government is giving.

Next we move down the social scale to the middle/lower middle class (known as C- in Venezuela):

This group is significantly larger, consisting of 15% of the population or 4 million people at the time. While its income is less than half of the previous group it still has a lot of expensive imported consumer items - 60% have cars, 65% have microwaves, 49% DVDs, 51% computers, and a still sizable 27% have credit cards. While no reference is made to it, probably some of these people can occasionally take trips abroad.

Clearly this group is going to be favored by the same sort of policies that favored by the top income group, just to a lesser degree.

Next we move out of the middle class and down to the working class or social class D:

This group made up 23% percent of the Venezuelan population or 6 million people (we will see shortly how those numbers have changed). This group is not only much bigger than the previous ones but it is also much less affluent. Rather than living in decent, if not very nice, housing as the previous groups do these people tend to live in run down private homes or public housing. Further, while they still generally have TVs and cell phone, only a minority of them own other imported consumer goods - 44% have microwaves, 27% DVDs, 24% have computers, and only 36% have their own cars. And only a very small minority have credit cards.

Further, although it isn't explicitly stated it is safe to assume people in this social class do not travel abroad at all. Not only could they never afford it, they would never be given a visa to entry any developed countries like the United States, Canada or the European Union.

Next we come to the final group - the poor and working poor, social class E:

This has for a long time been the socio-economic class of most Venezuelans encompassing 58% of the population and more than 15 million people.

These are people who are doing little more than getting by and who populate the huge hillside slums of Caracas and the other very numerous poor areas throughout Venezuela. They may get enough to eat and have clothes on their back (though significant portion don't even have those things) but they have very little in the way of consumer goods: only 18% have microwaves, 11% DVDs, 8% have computers, and only 18% have their own cars. A mere three percent have credit cards. And, of course, these people are not hopping on airplanes and traveling overseas.

Although we will go into greater detail shortly we can see here a fairly clear dividing line - the first two groups ABC, and C- are very big consumers of imported items and account for just about all travel abroad. Further, they are the only groups where the majority of people own private automobiles. The latter two groups, D and E, which together represent the vast majority of the population, consume far fewer imported items, don't travel abroad and generally don't have cars.

It is therefore clear that the first group makes heavy use of dollars via imports and travel and also makes heavy use of free gasoline via the cars they own so I will call them heavy consumers. The second group consumes far fewer imported items and hence is much less dependent on access to dollars. Further, they use relatively little of Venezuela's free gasoline as they generally don't own automobiles. I will therefore call them light consumers.

There are two more slides that we should look at before drawing any conclusions.

The first shows how the size of these socio-economic groups has changed recently:

Note that the heavy consumers, groups ABC+ and C-, didn't change much between 2004 and 2007. In 2004 they totaled 19% of the population and this year they increased to 20.7%. Clearly, these heavy consumers are still a small minority, barely more than a fifth of the total population.

Next note that the total number of light consumers, groups D and E, also didn't change much. In 2004 they totaled 81% and currently they constitute 79.3% of the population. The main change was within this grouping where a significant number of people who had been poor or working poor were able to move up to the working class.

Still the dividing line between heavy consumers and light consumers is pretty clear and unchanged - about 20% are heavy consumers and 80% are light consumers.

Finally lets look at their political tendencies:

This polling information from Datanalisis shows that the greatest level of support for the government is among classes D and E (the red circles) while the greatest opposition to the government is among the high income A and B groups (the blue circle).

If that data was maybe a little muddled by controversial constitutional reform proposal it can be seen much more clearly at the bottom where the data from before last years presidential election was given. There we clearly see that only a very small portion of the heavy consumers (A,B and C classes) support Chavez whereas large majority of the light consumers support Chavez.

In summary, heavy consumers are clearly anti-Chavez and constitute the oppositions political base while light consumers heavily favor Chavez and are his political base. Therefore, anything that were to adversely effect the light consumers would probably be political suicide for Chavez while policies that adversely effect heavy consumers would cause him little political harm.

With this in mind lets review some of the proposals from my last two posts.

In the first post it was pointed out half a billion dollars were being sent overseas to family members, another half a billion was spent on airlines, and a whopping $4.2 billion was spent for dollar transactions on credit cards. I stated that it would be wise for the government to either eliminate or curtail these expenditures. From an economic point of view it would make a lot of sense as it could save the country billions of dollars that could be better spent other items or simply saved.

But would restricting these expenses be politically viable? Well the dollars spent on airlines and sent overseas to relatives would clearly only effect the heavy consumers - they are the only ones who travel abroad. Further, restricting the use of credit cards for dollar purchases would only effect the upper classes also. Remember, 38% of classes A,B and C- and 27% of class C- have credit cards while only 9% of social class D have them and a minuscule 3% of social class E have them.

From this is should be very clear, that reducing the dollars allowed for overseas travel and dollar purchases with credit cards should NOT present a political problem for Chavez as those measure will almost exclusively impact those who don't support him in the first place.

So from a economic AND political viewpoint it would seem a no-brainer to go ahead with these measures.

In the following post I proposed raising the price of gasoline for private automobiles as a way of saving the Venezuelan government billions of more dollars. Also recall, I proposed continuing the same discounted prices for fuel used by buses and trucks so that this would only impact those with their own cars.

Looking at the data above it is clear this would impact the heavy consumers much more than the light consumers, but the divide isn't as clear as it was with overseas travel and credit cards.

Note that automobile ownership rates for heavy consumers are 74% for classes ABC- and 60% for class C-. Clearly raising gasoline prices will hit heavy consumers hard and they are likely to protest against it. But given that very few of them support Chavez in the first place, 6% of the former and 23% of the latter, that shouldn't impact Chavez's political fortunes.

By way of contrast, only a minority of light consumers have cars, 36% of social class D and 18% of class E. Most people in this group don't have cars.

Still, in contrast to the previous case where almost no light consumers travel abroad or have credit cards, in this case a significant number of them do have cars. That means that some of them WOULD be hard hit by a gasoline price increase and there would be at least some political repercussions for Chavez in carrying out this measure.

However, the losses through via making gasoline essentially free are huge (at least $20 billion!!) and even recovering a portion of those losses is simply too big a bonus for the country for it NOT to be done.

All this said, the cost saving measures that have been proposed clearly are politically viable as they would primarily impact those opposing Chavez and leave his political base untouched. However, the impact is uneven with a gasoline price hike being more politically costly to Chavez than the other measures.

That suggests one possible course of action. The government could first restrict the dollars for travel abroad and credit card purchases. By doing so they could save at least $2.5 billion dollars and possibly as much as $5 billion. These funds could then be dedicated to measures which would show immediate benefits to the population.

For example, this year little more than $2 billion was spent on food imports. If the money saved from restricting travel and credit cards were dedicated exclusively to food purchases the government could easily double or even triple the amount of food it brings in and sells through Mercal. Doing this would help solve a very immediate problem effecting people and buy it much political good will.

Then 6 months to a year after doing that the government could implement the more painful measure of raising gasoline prices. By then the government should have earned enough good will through its previous measure to withstand any political fallout from this reform. These savings, which as we saw could be up to $6 billion dollars annually, could then be dedicated to public works and industrialization projects which would also show benefits to the public over the longer term.

Of course, this is only one possible way of doing things and the government could choose other options and timing. But the central point is clear - these necessary economic reforms ARE politically viable and could even boost Chavez's political standing if done properly. Political timidity and fear should NOT be used as an excuse not to pursue these type of necessary reforms.

Lets also be clear about one further point. The Venezuelan government is NOT facing any kind of immediate economic crisis. The economy has been growing very rapidly in recent years, peoples standard of living has been increasing, and most people are happy with the state of the economy. This is likely to continue for at least the next year or two.

However, and this is a huge however, it is just as clear that there are problems which are getting worse and will continue to get worse over time - an overvalued currency, stagnant non-oil exports, a unproductive and unsustainable consumption binge, etc. It is probable that these problems will become a crisis over the longer term if not addressed soon. This means the Venezuelan government has two options:

A) deal with the problems now while they are still relatively small, the solutions won't be too politically costly, and their are no major elections for a number of years

or

B) ignore the problems, face a significant economic crisis in a few years if oil prices decline or even level off, and face this crisis right when Chavez faces the possibility of being recalled or the National Assembly is up for re-election.

Which do you think is better, not only from an economic point of view but also from a political perspective?

If you were Chavez, which option would you choose?

|