Tuesday, February 20, 2007

It takes one to know one

Last week I poked fun at a opposition supporter for just making up numbers when trying to show how Venezuelan suppliers are losing money selling meat at prices controlled by the government. Fortunately Ultimas Noticias took the trouble to come up with actual numbers:

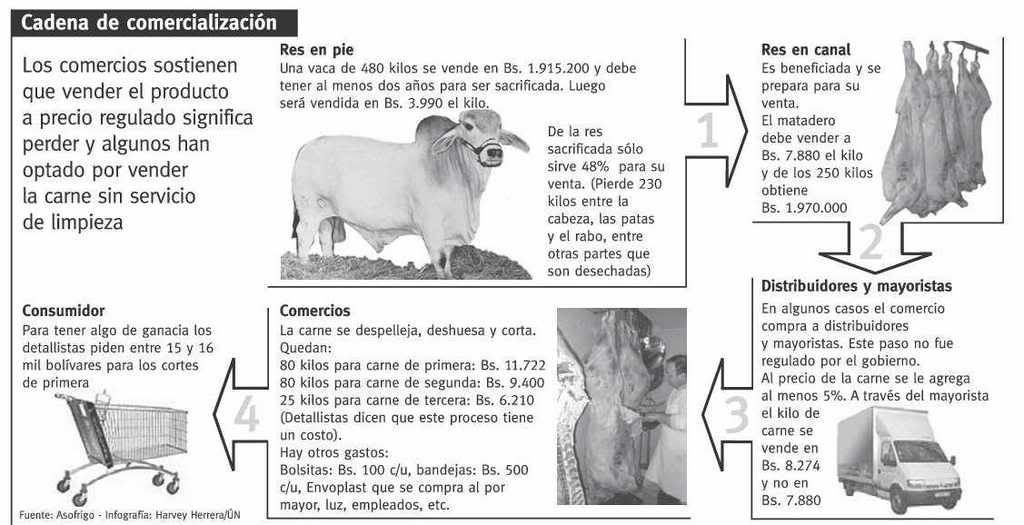

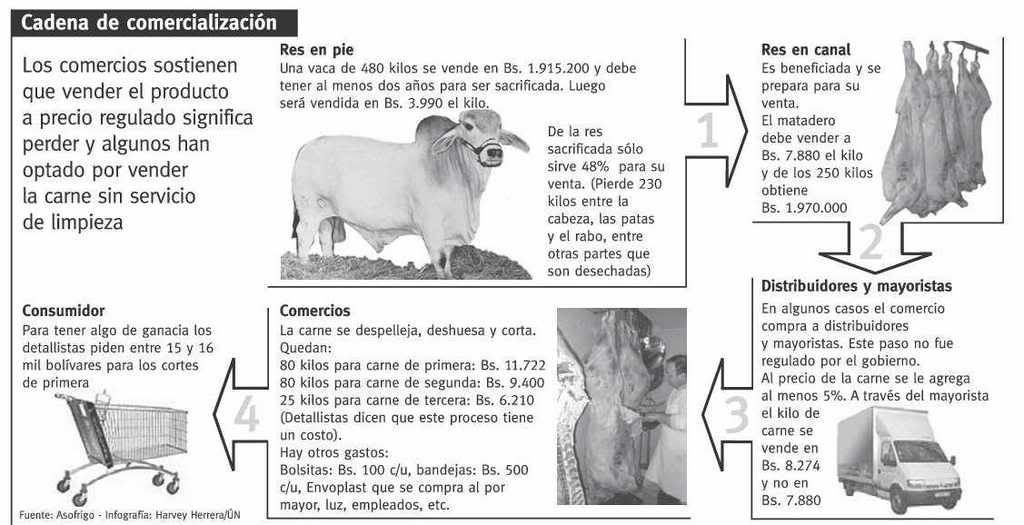

This diagram follows the meat prices through the process. The cattle are sold to the slaughterhouse at about 3,990 bolivars per kilo. The slaughterhouse then turns around and sells the meat at 7,880 bolivars per kilo. But as only half the mass of the cattle is usable the slaughterhouse is actually selling for barely more than it paid for it; 1,970,000 bolivares for the meat from one cow versus the 1,915,200 bolivares the slaughterhouse paid for it to begin with. That certainly isn’t much to cover their expenses and profit.

Now this price of 7,880 bolivares per kilo is exactly what the meat markets and grocery stores are supposed to pay for it according to the government. Yet there is a wholesaler between the slaughterhouse and the retail stores that tacks on another 5% bumping the price up to 8,274 bolivares. Right there the price controls have been broken as the retailers only get meat if they overpay for it.

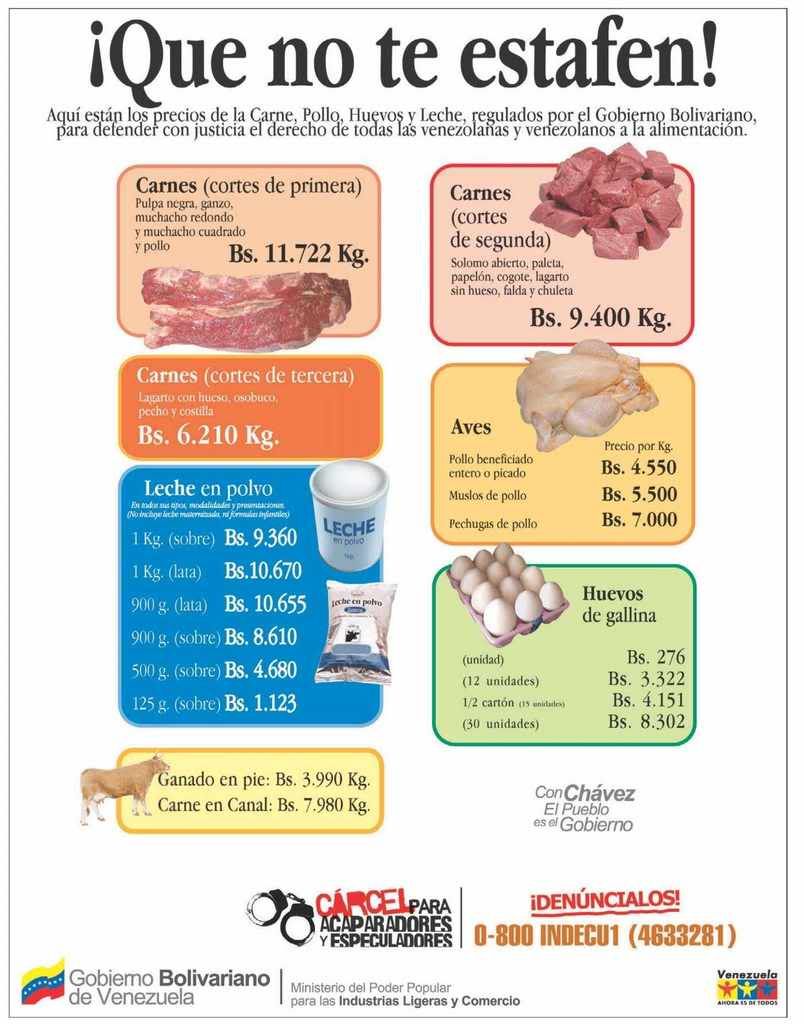

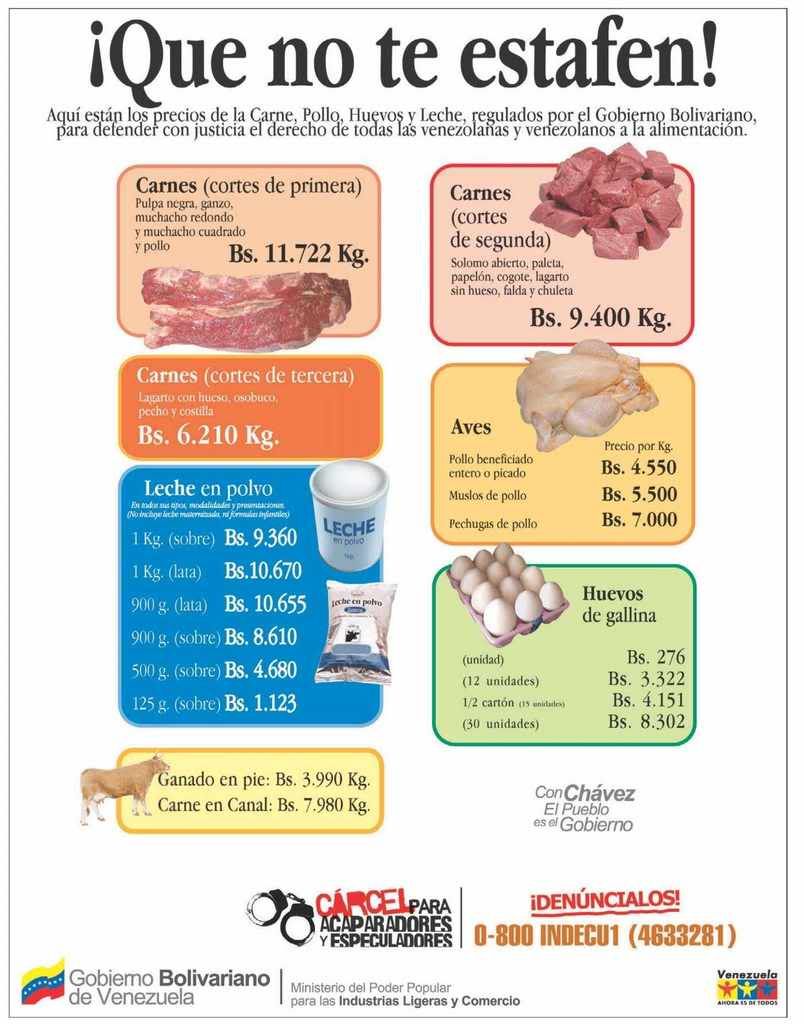

That then leads to retailers to overcharge. There are strict controls on the final price to the consumer as is seen in this (rather threatening) advertisement by the government:

The meat is broken into three classifications with prime meet having a controlled price of 11,722 bolivares, diced or ground meet selling for 9,400 bolivares and the lowest quality meet going for 6,210 bolivares per kilogram.

The problem is that the retailers complain they can’t make a profit unless they sell it for 15,000 or 16,000 bolivares. They say that they have to sell at those prices to cover the cost of buying the meat at 8,200 per kilo. To sell at the regulated prices they would have to be able to get it for 6,200 per kilogram. Because they say they can’t sell it at the regulated prices they don’t sell at all – hence the empty meat displays.

However, the industry federation for the beef industry, Asofrigo, claims there is plenty of beef, that they are selling it in the market at the regulated price, and that they are slaughtering 5,000 to 6,000 cattle per day.

Who is telling the truth? Is there a genuine shortage created by price controls? Could be. Or is there hoarding by people who don’t like seeing their profits constricted and are intentionally creating shortages as a way to pressure the government to back off its controlled prices? If so it wouldn’t be the first time, and the government finding warehouses full of other supposedly scarce items does make one wonder. But the price numbers given in this analysis simply aren’t precise enough for us to know. Moreover, this price information comes from people involved in producing and marketing meat and who therefore have every incentive to manipulate the information they provide.

In reality what this does show is what the government is up against trying to regulate prices in a market economy – it is very difficult and requires the government to be able to gather and evaluate all sorts of information very quickly and efficiently. That isn’t something that governments are known for being able to do.

Further, as has been pointed out very nicely by others price controls create problems and distortions of their own. The reality is, they are not an effective means for the government to control the economy or give subsidies to needy sections of the population. They create distortions, are impossible to administer, and they aid everyone without regard to income, which surely shouldn’t be the governments intention in the first place. The rich can afford to pay top Bolivar for their meat!

I have noted this recurring problem with the Chavez government. They often adopt what may be appropriate measures to deal with a crisis – exchange controls, price controls, prohibitions against laying off employees, etc. – but then leave them in effect long after the crisis has passed. Most all these measures were adopted during the crisis brought about by the opposition strike of 02/03 and may have been appropriate at that time but we are now four years removed from that event and these measures still remain in effect in spite of the fact that the economy is booming.

Do workers really need to be protected against layoff when the economy is expanding and hundreds of thousands of new jobs are being created annually? Do prices need to be controlled when the purchasing power of Venezuelans is skyrocketing? If these emergency measures can’t be lifted now when the economy is about as far away from an emergency as it will ever get when will they ever be lifted?

Now, it may be pointed out that entire sections of the Venezuelan economy are dysfunctional, being controlled by oligopolies and there is no free competition to protect consumers from being gouged. It is possible that is true. But then the appropriate response isn’t for the government to take on mission impossible - effectively setting prices throughout the economy.

A better and more effective solution would be to speed up land reform, create more new farms and farming co-operatives, provide more capital to these new farmers and then let them produce the new food that Venezuela needs and that will bring prices down.

The Venezuelan economy, in spite of what one would believe from listening to the opposition, is very much a market economy. Market economies are very efficient under certain circumstances but among other deficiencies they don’t always create desirable outcomes. But a clever government rather than dealing with this by attempting to dictate to the market what to do, trying to heard cats in effect, will use the market to its advantage by creating the market conditions it wants.

So if the Venezuelan government wants to make sure food in Venezuela is less expensive there is a pretty much 100% guaranteed way to do that – make sure there is lots of food being made by lots of different producers. If the oligopolies of a few entrenched producers try to get in the way just wipe them out the good old capitalist way – through competition. For a thinking government, sometimes socialism will be the solution. But sometimes the solution is simply for there to be more capitalism. This is one of those situations.

Now, people may be wondering where the title of this post came from. I really appreciate irony and the world is full of it – the Venezuelan government being no exception. It certainly hasn’t escaped my attention that the same government that in effect makes its living off of high oil prices brought about by hoarding (see the previous post on OPEC) is so quick to cry foul when some meat producers may be hoarding their goods to get higher prices. In this case it appears what is good for the goose isn’t so good for the gander!

Anyways I guess it should come as no surprise why the government is so good at sniffing out hoarders – it takes one to know one!

|

This diagram follows the meat prices through the process. The cattle are sold to the slaughterhouse at about 3,990 bolivars per kilo. The slaughterhouse then turns around and sells the meat at 7,880 bolivars per kilo. But as only half the mass of the cattle is usable the slaughterhouse is actually selling for barely more than it paid for it; 1,970,000 bolivares for the meat from one cow versus the 1,915,200 bolivares the slaughterhouse paid for it to begin with. That certainly isn’t much to cover their expenses and profit.

Now this price of 7,880 bolivares per kilo is exactly what the meat markets and grocery stores are supposed to pay for it according to the government. Yet there is a wholesaler between the slaughterhouse and the retail stores that tacks on another 5% bumping the price up to 8,274 bolivares. Right there the price controls have been broken as the retailers only get meat if they overpay for it.

That then leads to retailers to overcharge. There are strict controls on the final price to the consumer as is seen in this (rather threatening) advertisement by the government:

The meat is broken into three classifications with prime meet having a controlled price of 11,722 bolivares, diced or ground meet selling for 9,400 bolivares and the lowest quality meet going for 6,210 bolivares per kilogram.

The problem is that the retailers complain they can’t make a profit unless they sell it for 15,000 or 16,000 bolivares. They say that they have to sell at those prices to cover the cost of buying the meat at 8,200 per kilo. To sell at the regulated prices they would have to be able to get it for 6,200 per kilogram. Because they say they can’t sell it at the regulated prices they don’t sell at all – hence the empty meat displays.

However, the industry federation for the beef industry, Asofrigo, claims there is plenty of beef, that they are selling it in the market at the regulated price, and that they are slaughtering 5,000 to 6,000 cattle per day.

Who is telling the truth? Is there a genuine shortage created by price controls? Could be. Or is there hoarding by people who don’t like seeing their profits constricted and are intentionally creating shortages as a way to pressure the government to back off its controlled prices? If so it wouldn’t be the first time, and the government finding warehouses full of other supposedly scarce items does make one wonder. But the price numbers given in this analysis simply aren’t precise enough for us to know. Moreover, this price information comes from people involved in producing and marketing meat and who therefore have every incentive to manipulate the information they provide.

In reality what this does show is what the government is up against trying to regulate prices in a market economy – it is very difficult and requires the government to be able to gather and evaluate all sorts of information very quickly and efficiently. That isn’t something that governments are known for being able to do.

Further, as has been pointed out very nicely by others price controls create problems and distortions of their own. The reality is, they are not an effective means for the government to control the economy or give subsidies to needy sections of the population. They create distortions, are impossible to administer, and they aid everyone without regard to income, which surely shouldn’t be the governments intention in the first place. The rich can afford to pay top Bolivar for their meat!

I have noted this recurring problem with the Chavez government. They often adopt what may be appropriate measures to deal with a crisis – exchange controls, price controls, prohibitions against laying off employees, etc. – but then leave them in effect long after the crisis has passed. Most all these measures were adopted during the crisis brought about by the opposition strike of 02/03 and may have been appropriate at that time but we are now four years removed from that event and these measures still remain in effect in spite of the fact that the economy is booming.

Do workers really need to be protected against layoff when the economy is expanding and hundreds of thousands of new jobs are being created annually? Do prices need to be controlled when the purchasing power of Venezuelans is skyrocketing? If these emergency measures can’t be lifted now when the economy is about as far away from an emergency as it will ever get when will they ever be lifted?

Now, it may be pointed out that entire sections of the Venezuelan economy are dysfunctional, being controlled by oligopolies and there is no free competition to protect consumers from being gouged. It is possible that is true. But then the appropriate response isn’t for the government to take on mission impossible - effectively setting prices throughout the economy.

A better and more effective solution would be to speed up land reform, create more new farms and farming co-operatives, provide more capital to these new farmers and then let them produce the new food that Venezuela needs and that will bring prices down.

The Venezuelan economy, in spite of what one would believe from listening to the opposition, is very much a market economy. Market economies are very efficient under certain circumstances but among other deficiencies they don’t always create desirable outcomes. But a clever government rather than dealing with this by attempting to dictate to the market what to do, trying to heard cats in effect, will use the market to its advantage by creating the market conditions it wants.

So if the Venezuelan government wants to make sure food in Venezuela is less expensive there is a pretty much 100% guaranteed way to do that – make sure there is lots of food being made by lots of different producers. If the oligopolies of a few entrenched producers try to get in the way just wipe them out the good old capitalist way – through competition. For a thinking government, sometimes socialism will be the solution. But sometimes the solution is simply for there to be more capitalism. This is one of those situations.

Now, people may be wondering where the title of this post came from. I really appreciate irony and the world is full of it – the Venezuelan government being no exception. It certainly hasn’t escaped my attention that the same government that in effect makes its living off of high oil prices brought about by hoarding (see the previous post on OPEC) is so quick to cry foul when some meat producers may be hoarding their goods to get higher prices. In this case it appears what is good for the goose isn’t so good for the gander!

Anyways I guess it should come as no surprise why the government is so good at sniffing out hoarders – it takes one to know one!

|